Concept of Production

Technological transformation of input (factor input: land labor, capital, organization & non-factor input: water, electricity, raw materials) into output (finished goods & services) is known as production.

In other words, production is the process of making goods to satisfy human wants. Production is also relating to the process of creating or improving utility or creation of exchange value.

Production Function

Production function is a purely technical relation which connects factor inputs and outputs. In other words, it is a schedule of quantity produced of a commodity at various levels of inputs for a specified period of time. Where, both inputs and outputs are measured in the physical terms rather than in monetary units.

Algebraically, production function is expressed as:

1. Q = f (N)

Where,

Q = output (dependent variable)

N = input (independent variable)

2. Q = f (Ld, L, K, O) ------------- Traditionally

3. Q = f (Ld, L, K, O, T, R, E, .......)

Where,

T = Technology

R = Raw Materials

E = Efficiency Parameter

4. Q = f (L, K) --------------- To simplify the production analysis

Types of Production Function

1. Short-Run (One Variable) Production Function

Q = f (Nvf,  )

)

Where,

Nvf = Unit of Variable Inputs

= Constant Unit of Fixed Inputs

= Constant Unit of Fixed Inputs

or,

Q = f (L,  )

)

2. Long-Run (Multi Variable) Production Function

Q = (Ld, L, K, O, M, T)

or,

Q = f (L, K)

Importance of Production Function in Business Decision

1. To Determine Least Cost Combination of Inputs

There are mainly labor-intensive and capital-intensive production technique. Production function is important to determine appropriate technique of production for least cost combination of inputs in the production process.

2. To Determine the Value of Employing a Variable Input

Worthwhile to use more variable factor, when MR>PL

Better to stop production, when MR = PL

3. To Take Long-Run Production Decision

Basically, operation of returns to scale in the production system determine long-run.

Difference Between Short-Run and Long-Run Production Function

Concept of TP, AP & MP

Total Product (TP)

TP is the amount of total output produced by a given amount of factor by a firm or an industry within a specific period of time.

In other words, TP is defined as the cumulative value of marginal product.

Symbolically,

TP = ΣMP

Where,

TP = Total Product

MP = Marginal Product

Similarly,

TP = AP X N

Where,

TP = Total Product

AP = Average Product

N = Units of Factor Input

Average Product (AP)

AP refers to the output per unit of input. It is found by dividing the TP by number of factor used (say labor).

Symbolically,

AP = TP/L

Where,

AP = Average Product

TP = Total Product

L = Units of Labor

Marginal Product (MP)

MP may be defined as the change in TP resulting from one additional unit of factor input.

In other words, it is the ratio of change in TP to change in a factor input (say labor).

Symbolically,

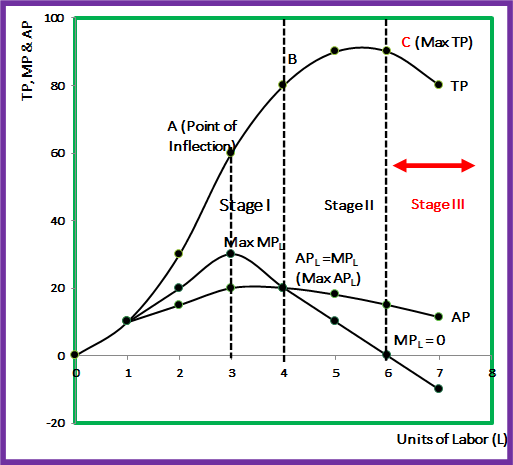

Derivation of TP, AP & MP Curve

Using above table, we can derive TP, AP and MP curve.

Derivation of TP Curve

In the above figure, initially TP increases at increasing rate and then it increases at decreasing rate. Finally it reaches to its maximum point then if we employ more labor, it starts to fall due to lack of sufficient capital.

Derivation of AP Curve

Initially AP increases and then it reaches to its maximum point. If we employ more labor, it starts to fall due to lack of sufficient capital but it never touches x-axis.

Derivation of MP Curve

Initially MP also increases and then it reaches to its maximum point. If we employ more labor, it starts to fall due to lack of sufficient capital.

When TP is maximum MP is equal to zero. Thereafter, if we again employ more labor, it becomes negative.

Law of Variable Proportion

Introduction

This law was first developed by Alfred Marshall, J. Stigler, F. Benham, P.A. Samuelson, K.E. Boulding. It is based on the short-run production function that examines the effect on production when the unit of one factor of production is increased, keeping other factors constant.

The short-run production function can be written as,

Q = f (L,

)

This law is an important economic principle used by economists to analyze input-output relation in the short-run under a condition of one variable factor (labor) and all other fixed factors (plant, equipment, land, management, and technology).

This law is also known as the law of the diminishing returns.

It states that if a producer increases the variable factor, output also increases up to a certain stage but ultimately it will fall; the rate of change in output may vary from one stage to another.

Initially output increases at increasing rate but after a certain point, the rate of increase in output diminishes and eventually it will be negative with the continued addition of the variable factor.

In the words of K.E. Boulding, "As the increase in the quantity of any one input which is combined with a fixed quantity of the other inputs, the marginal physical productivity of the variable input must eventually decline".

The law shows the behavior of output as the quantity of one factor increased, keeping the quantity of other factors fixed, the marginal and average product will ultimately decline.

The law is named as variable proportion because in the production system the ration of fixed and variable varies (changes).

This is illustrated in the below table.

The amount of capital is fixed at 10 units and units of labor are increased in each time of production. With the increase in labor (1 to 2, 2 to 3, and 3 to 4) but constancy in the amount of capital (10), capital-labor ratio changes and it declines.

Assumptions

1. Rational Producer

A producer who aim to maximize profit and has perfect knowledge about the market.

2. Short-Run

This law is applicable in short-run. All the resources apart from one variable are held unchanged in quantity and quality because time is too short for a firm to change the quantity of fixed factors.

3. Single Variable Factor

One factor (labor) input is assumed to be variable and that variable factor can be changed in fixed proportion only.

4. Homogeneous Variable Factors

Each factor unit of variable factor is identical in amount and quality.

5. Fixed Amount of Other Factors

There must be some inputs (plant, equipment, land, management, and technology) whose quantity is kept constant.

6. Input Prices Remain Constant

This law assumes that all the factor and non-factor price remains constant.

7. Factor Proportions are Changeable

This law shows the effects on output by altering factor proportion. The law of proportionality assumed that the proportion between fixed and variable factor is changeable. If factors of production are to be combined in a fixed proportion, the law has no validity or the does not apply if all factors are proportionately varied.

8. Constant or Stable Technology

If there is an enhancement or improvement in technology the production function will obviously move in the upward direction and MP and AP may rise instead of diminishing.

Explanation with Table and Diagram

On the basis of the above assumptions, this law can be illustrated with the following table and figure.

Suppose there is a given amount of capital in which more and more labor (variable factor) is used to produce good.

These data do not relate to any particular firm (i.e. the data are hypothetical). The TP results by combining each level of labor input with an assumedly fixed amount of capital. The MPL is the change in TP in response to one-unit change in labor input. With on labor inputs, TP is zero; with the active aid of human labor, there would not be the mobilization of other factors of production.

The first, second and third unit of labor reflect increasing returns, their MP being 10, 20 and 30 units respectively. Then, beginning with the fourth labor, MP (the increase in TP) diminishes continuously and actually becomes zero with the sixth unit of labor and negative with the seventh.

This law is also explained by following diagram.

It is important to note that, so long as MP is positive, TP is increasing. And when MP is zero, TP is at its peak. Finally, when MP becomes negative, TP is declining. Increasing return is reflected by a rising MP, diminishing returns by a falling MP.

3 Stages of Law of Variable Proportion

Stage I: Increasing Return Phase (From Point 0 to B)

In this stage, the TP and AP rapidly increases and MP is maximized, when three units of labor are used. The AP is maximum when AP and MP are equal, that is, when four units of labor are used. When AP is maximized the first stage ends. At stage I, MP is greater than AP i.e. MP>AP.

Initially TP increases at increasing rate form point 0 to A and then TP increases at diminishing rate from A to B . TP is concave upward till the point A and TP is concave downward beyond point A. So, point A is the point of inflection.

In short, TP increases, AP and MP also increases but MP reaches at maximum and starts to decline within this stage.

Causes of Increasing Return Phase (L<K)

1. Scarce Variable Factor (L) and Excess Supply of Fixed Factor (K)

In the initial process of production the increasing return phase appears due to the inadequacy of the variable means compared to the fixed means.

2. Efficient Utilization of Fixed Factor

At the beginning, the fixed factors are underutilized. When more and more units of variable factors are added, utilization of indivisible fixed factor increases rapidly and production rate increases fast.

3. Right Combination

The right combination of factors can be made by increasing variable factors because at the beginning units of K is more compared with L.

4. Efficiency of Variable Factor

As more labors are employed, the efficiency of labor itself increases because of the advantages of division of labor and specialization in work.

5. Use of Alternative Energy

Use of non-human and non-animal power such as water, wind power, hydroelectricity, atomic energy etc. reduces cost of production and rate of return increases.

Stage II: Diminishing Return Phase (From Point B to C)

This stage starts after the maximum of AP and ends at the maximum of TP where MP = 0. In this stage, TP continuous to increase at a decreasing rate till it reaches to its maximum value. MP and AP decreases but remain positive. At this stage II, AP is greater than MP i.e. MP<AP.

In brief, TP increases, AP and MP both decreases and TP becomes maximum and MP = o at the end of the stage.

Causes of Diminishing Return Phase

1. Inadequacy of Fixed Factor

If more and more amount of the variable factor (labor) are employed with the fixed factor, the fixed factor becomes inadequate after a certain extent relative to the variable (labor) and cannot employ the additional variable factors efficiently as in the initial phase. Thus, MP of the variable factor diminishes.

2. Indivisibility of the Fixed Factor

The indivisible factor has a certain limit to employ variable factor. It is optimally utilized up to the point where AP is maximum. Once the optimum proportion is disturbed by further increases in the variable factor, returns per unit of variable factor will diminish primarily because the indivisible factor is being used in wrong proportion with the variable factor.

If the fixed factor would be of divisible character, we could combine it in required quantity by breaking it in small quantity for less variable factor or greater quantity of fixed factor could be used with larger quantity of variable factor. It this could have been possible there would not be increasing or decreasing returns in the production. In this context, M.M. Bober says, "Let divisibility enter through the door, law of variable proportion rushes out through the window".

3. Imperfect Substitutability of the Factors.

One factor cannot be perfectly substituted for another because they have their own uses in the production. Both factors are essential for production. If it is possible to use one factor for another there is the need of different factors. In this law, we may substitute the fixed factor by variable factor if fixed factor becomes scarce. But, it is not possible and the law of diminishing return operates.

Stage III: Negative Returns Phase ( Beyond point C)

This stage starts after the maximum TP where MP = 0. In this stage, TP also starts to fall, AP and MP also fall but AP is still positive where MP becomes negative.

In brief in this stage TP, AP and MP decreases and MP becomes negative.

Causes of Negative Return Phase

1. Overcrowding Effect

If we keep on adding variable factors like labor on a given quantity of fixed factor (land), this will lead to overcrowding on the fixed factor. There will be therefore, insufficient availability of tools and equipment per worker, which causes fall in production.

2. Managerial Problem

Use of too many variable factors like labor also crates the problem of effective management. When there are too many workers, they may shift responsibilities on to other. It becomes difficult to fix responsibility. The labor can therefore avoid work. The proverb "Too many cooks spoil the broth" also prove this stage.

Stage Summary

Stage of Operation of the Firm

The answer is definitely in stage II for a rational producer but without introducing output prices we cannot exactly say which volume of output is the optimum.

In stage I, there is increasing returns till the maximum AP and TP is increasing although with decreasing rate. There is further possibility to increase profit beyond this stage. Thus, a rational producer does not stop production in stage I.

It must be clear that a rational producer never operates in stage II even if the variable factor (L) is free because the producer would be producing less and would be using more units of the variable input (L). Operation in stage II results loss (TP decline) to the producer due to negative MP and negative marginal returns.

Therefore, rational decision of the producer is to operate in stage II.

Applicability of the LVP in Agriculture

The law of variable proportion is universal as it applies to various field of production where some factors are fixed (land, mines, machines, fisheries, house and building) and other are variable.

Therefore, this law holds well in all activities of production like agriculture, mining, manufacturing industries, if they are expanded beyond the optimum point.

But, it is true that the law of variable proportion operates quickly in agriculture and lately in manufacturing industry.

There are several reasons why this law applies more generally to agriculture which are as follows:

1. Influence of Natural Condition

There is great influence of nature in agriculture. The best human efforts may be neutralized by adverse natural influences.

2. Limited use of Machine

There is limited use of machine in agriculture. So, the economic efficiency of specialized machinery cannot be obtained in agriculture.

3. Limited Scope of Division of Labor

Farming activities does not require highly skilled labor. So, there is limited scope of division of labor. Hence, the advantages of division of labor are lost.

4. Large Area

Agriculture operations are spread over a very large area and supervision is difficult. This will reduce the productivity.

5. Productivity of the Soil

Soil gets exhausted due to continuous cultivation and leads to the operation of the law of diminishing returns.

Importance of Applicability of the Law of Variable Proportion

It is a law of economic life and can be applicable in the field of production as it has theoretical reasoning and extensive practical evidence/implications. It is helpful in understanding clearly the process of production explaining the input-output relations.

The law tells us that any increase in the units of variable factor will lead to increase in the TP at a diminishing rate.

Until Marshall's period, it was though that this law applied to only agriculture. The following are the brief descriptions of the theories developed by various economists that are based on the concept of diminishing returns.

1. Malthusian Theory of Population

Especially developing countries faces food shortage and overpopulation problem when there is rise in population. Because Malthusian theory of population states that population increases faster than the food supply, is obviously based on the fact that the production of food is subject to the law of diminishing returns.

2. Ricardian Theory of Rent

The Ricardian theory of rent explains the determination of rent on the assumption that inferior land has to cultivate on account of the operation of law of diminishing returns.

3. Theory of Distribution

The marginal productivity theory, which determines the share of factor of production in the national dividend, is also based on the operation of this law.

The law is of fundamental importance for understanding the problems of underdeveloped countries (UDCs). In such agricultural economies, the pressure of population on land increases with the increase in population. This leads to declining or even zero or negative MP. This explains the operation of the law of diminishing returns in UDCs in its intensive form.

Ragner Nurkse have suggested ways to make use of those disguisedly unemployed labor by withdrawing them and putting them in those occupations where the marginal propensity is positive.

Limitations or Postponement of the Law of Variable Proportion

The condition where this is not applicable or we can postpone the applicability of diminishing return are as follows:

1. Improvement in Technique of Production

This law is applicable when production technology remains constant. But, we can suspend the operation of diminishing returns by continually improving the variable factors, technique of production through the progress in science and technology.

2. Perfect Substitute

This law of variable proportion can also be postponed in case factors of production are made perfect substitutes i.e. when one factor can be substituted for the other.

3. New Soil

When a virgin soil is brought under cultivation, MP will increase for a time. So, in case of a new soil, the law does not apply in the beginning.

4. Long-Run

This law is applicable when at least one factor is variable and other are fixed. If other factor such as capital is increased, the marginal return will go up at first instead of diminishing .

Law of Returns to Scale

Introduction

This law is long run production theory which assumes all factors of production are variable i.e. Q = f(L, K). The law of returns to scale refers to the effects of a change in the scale of factors (inputs) upon output in the long run when the combinations of factors are changed in the same proportion. So, the law of returns to scale refers to the effects of scale relationship.

If by increasing two factors, say labor and capital, in the same proportion, output increases in exactly the same proportion, there are CRS. If in order to secure equal increases in output, both factors are increased in larger proportionate units, there are DRS. If in order to get equal increases in output, both factors are increased in smaller proportionate units, there are IRS.

This law can also be explained in terms of the Iso-Quant (IQ), TP or MP approach. According to this law, when all the inputs are increased in the same proportion, TP may increase at an increasing rate, at a constant rate or at a diminishing rate. It defines the total effect on output with proportionate change in all factors of production.

Assumptions

1. Rational Producer

A producer who aim to maximize profit and has perfect knowledge about the market.

2. Variable Factor

Two inputs labor and capital are variable and single commodity output say X.

3. Constant Proportion

Labor and capital should be change in same proportion only.

4. Physical Unit

Output is measured in physical terms (quantities) rather than monetary unit.

5. Homogeneous Factor Input

All the factor input are homogeneous (same quality).

6. Long-Run Production Function

It is based on long-run production function where producer have sufficient time to manage all factors.

7. Perfect Competition in Labor and Product Market

As like in perfect market, there is also large number of buyer & seller, constant price, perfect knowledge, free entry & exit in labor and product market.

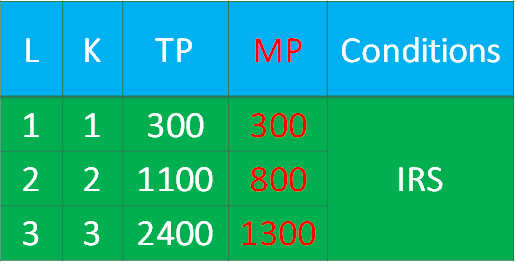

Explanation with Table and Diagram

On the basis of the above assumptions, this law can be illustrated with the following table and diagram. Suppose all the factor inputs are increased in equal proportion, there are three stages in production. They are:

A. Increasing Returns to Scale (IRS): Increase in output at greater proportion than the increase in input.

B. Decreasing Returns to Scale (DRS): Increase in output at smaller proportion than the increase in input.

C. Constant Returns to Scale (CRS): Output changes by same proportion as inputs.

A. Increasing Returns to Scale (IRS)

If total output of a firm increases in greater proportion than the increase in factor inputs, it is said to be IRS. In other words, if output increases in more percentage than the percentage change in factor inputs, then it is the IRS. For example, 100 % ↑ in factor input ➝ 125%↑ in output. It can be explained with the following table and diagram.

The table shows the IRS because it indicated that TP and MP of a firm is increased in greater proportion than to the increase in units of labor and capital. When 1L and 1K were used, the TP of a firm is 500 kg. As firm increases inputs by 100%, the TP of the firm is increased by more than 100% i.e. from 500 to 1200 to 2500 respectively.

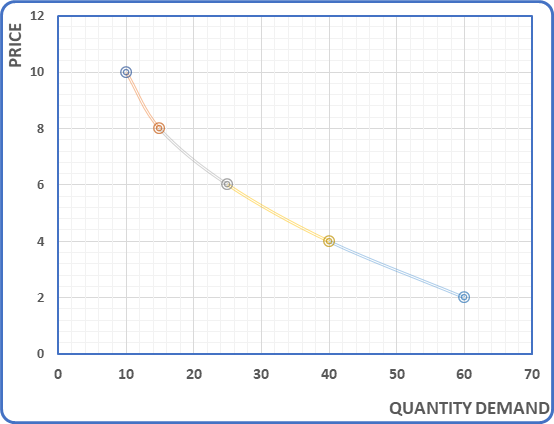

It can also be presented diagrammatically as:

In the graph, TP is increasing in greater proportion with the increase in units of labor and capital. The upward and positively sloped curve shows IRS. The combination points A, B & C shows the increasing trend of TP.

Causes of IRS

1. Indivisibilities of Technical and Managerial Factors of Production

The indivisible (not divided into small size) factors like managerial skills of manager and machinery (engine) available in a given size and have to be employed in a minimum size even if scale of production is much less than their capacity output i.e. utilized below their capacity. Therefore, by increasing all inputs, the productivity of indivisibility factors is increased and results in IRS.

2. Higher Degree of Specialization

Specialization of both labor and managerial cadre, which becomes possible with increase in scale of production. The use of specialized labor and management increases productivity per unit of inputs in cumulative way. In the long-run producer may hires such specialized labor, managerial cadre, advance technology as well as machinery.

3. Managerial Economies

When the production is on a large scale, the management work can be divided on function basis such as production, marketing, finance, sales, R&D etc. and each function can be allotted to a specialized manager. Division of work in various departments causes production increase rapidly.

4. External Economies

When the industry itself expands, external economies appear. As a large number of firms are concentrated at one place, skilled labor, credit (by the BFIs with low interest rate without collateral and securities) and transport facilities are easily available. Subsidiary industries, research and training cetres crop or appear which help to increase the productivity of the firms.

5. Dimensional Relations

Due to internal and external economies, as the firm expands, dimensional effect arises. For example, when size of a room (15'x10' = 150 sq. fit) is doubled (30'x20'), the area of the room is more than doubled, i.e. 30'x20' = 600 sq. fit. Similarly, when the diameter of the pipe is doubled, the flow of water is more than double. Following this dimensional relationship, when the labor and capital are doubled, the output is more than doubled over level of output.

B. Constant Returns to Scale (CRS)

If total output of a firm increases in same proportion as the increase in factor inputs, it is said to be CRS. In other words, if output increases in same percentage as the percentage change in factor inputs, then it is the IRS. For example, 100%↑ in factor input➝ 100%↑ in output. It can be explained with the following table and diagram.

The table shows the CRS because it indicates that TP is increasing in same proportion with the increase in units of labor and capital. When 1L and 1K were used, the TP of a firm is 500 kg. As firm increases inputs by 100%, the TP of the firm is also increased by 100% i.e. from 500 to 1000 to 1500 respectively.

It can also be presented diagrammatically as:

In the graph, TP is increasing in same proportion with the increase in units of labor and capital. The upward and positively sloped curve shows CRS. The combination points A, B and C shows the increasing trend of TP with CRS.

Causes of CRS

1. Absence of Economies

During this stage, the economies start vanishing and diseconomies arise as a natural process when a firm expands beyond certain stage. Both economies and diseconomies of scale are exactly in balance (neutralized) over a particular range of output. Due to this, CRS operates in production.

2. Optimum Factor Proportion

While on combining other factors of production with indivisible factors of production, it may create optimum factor proportion or optimum allocation of resources. And, increasing the scale of such optimum factor gives rise to CRS in production.

3. Divisible, Substitutable and Homogeneous Factors

When factors of production are perfectly divisible, substitutable, and homogeneous with perfectly elastic supplies at given prices, the returns to scale are constant and the production is homogenous of degree one.

C. Decreasing Returns to Scale (DRS)

If total output of a firm increases in smaller proportion as the increase in factor inputs, it is said to be DRS. In other words, if output increases in smaller percentage as the percentage change in factor inputs, then it is the DRS. For example, 100%↑ in factor input ⟶ 80%↑ in output. It can be explained with the following table and diagram.

The table shows the DRS because it indicates that TP is increasing in smaller proportion with the increase in units of labor and capital. When 1L and 1K were used, the TP of a firm is 500 kg. As firm increases inputs by 100%, the TP of the firm is increased by only 80% i.e. from 500 to 900.

It can also be presented diagrammatically as:

In the graph, TP is increasing in smaller proportion with the increase in units of labor and capital. The upward and positively sloped curve shows DRS. The combination points A, B, and C shows the increasing trend of TP with DRS.

Causes of DRS

When a firm expands beyond proper limits DRS operates in the production system. Some reasons behind DRS are as follows:

1. Internal Diseconomies

- Indivisible factors may become inefficient and less productive.

- Managerial Difficulties: The difficulty of organizing, coordinating, and integrating activities increases with the increase in size (scale) of the firm. Problems like lack of proper coordination; lengthy chain of communication and command between the top management and men on the production line etc. decreases the overall efficiency of management.

- Full Utilization of Entrepreneur Skill: When the abilities and skills of entrepreneur may be fully utilized. An increase in scale beyond this level may decrease the efficiency of entrepreneur and gives rise to diseconomies of scale.

- Labor Diseconomies: Increased number of laborers encourages labor union activities. As a result, there is loss of output per unit of time.

2. External Diseconomies

- Raise in Factor Prices and Raw Material: As the industry continuous to expand, the demand for skilled manpower and capital increases and it raises the factor prices. Similarly, increase in price of raw material may lead DRS.

- Transport and marketing difficulties arise

- Excess Competition among Firms: Entry of new firm in the market creates competition and due to this, factors of production like land, capital, skilled/efficient manpower and raw materials will be scare.

- Limitedness or Exhaustibility (Scarcity) of the Natural Resources: Doubling of coal mining plants may not double the coal deposits. Similarly, doubling the fishing fleet may not double the fish output because the availability of fish may decrease when fishing is carried out an increasing scale.

- Use of Inferior Factors: Inferior or less efficient factors may be brought into use due to scarcity of the natural resources. For example, when mining operations are extended to inferior, distant or deeper mines, scale of production decrease.

- Pecuniary (Financial) Diseconomies: When the scale of production expands the discount and concession on bulk purchase of input reduced.

TP Approach

Increasing Returns to Scale

Constant Returns to Scale

Decreasing Returns to Scale

Increasing Returns to Scale

Constant Returns to Scale

Decreasing Returns to Scale

)

= Constant Unit of Fixed Inputs

)

Comments

Post a Comment

If you have any doubt, Please let me know !